Mortar Strength Categories in Historical and Contemporary Masonry

Mortar strength profoundly influences how masonry walls manage movement, moisture, and long-term durability. Traditional European construction used extremely weak lime mortars, whereas modern practice favors much stronger Portland cement mixes. Selecting the correct strength is fundamental to successful restoration and compatible new construction.

Introduction

In any masonry assembly, the mortar must remain softer and more permeable than the brick or stone it binds. This principle governed European building practice for centuries and continues to guide conservation work today. The shift from soft lime mortars to rigid Portland cement mortars in the late 19th century dramatically changed wall behavior and introduced new failure mechanisms.

Historical Lime Mortars (Pre-1900)

Before Portland cement became widely available, mortars throughout Europe and early North America consisted almost entirely of lime putty or natural hydraulic lime mixed with sand.

Compressive strength: typically 50–250 psi (0.3–1.7 MPa)

Extremely high vapor permeability allowed walls to dry effectively

Excellent flexibility accommodated thermal expansion, settlement, and minor structural movement

Autogenous healing occurred as free lime slowly carbonated and sealed hairline cracks

These properties enabled centuries-old masonry to survive without widespread spalling or cracking

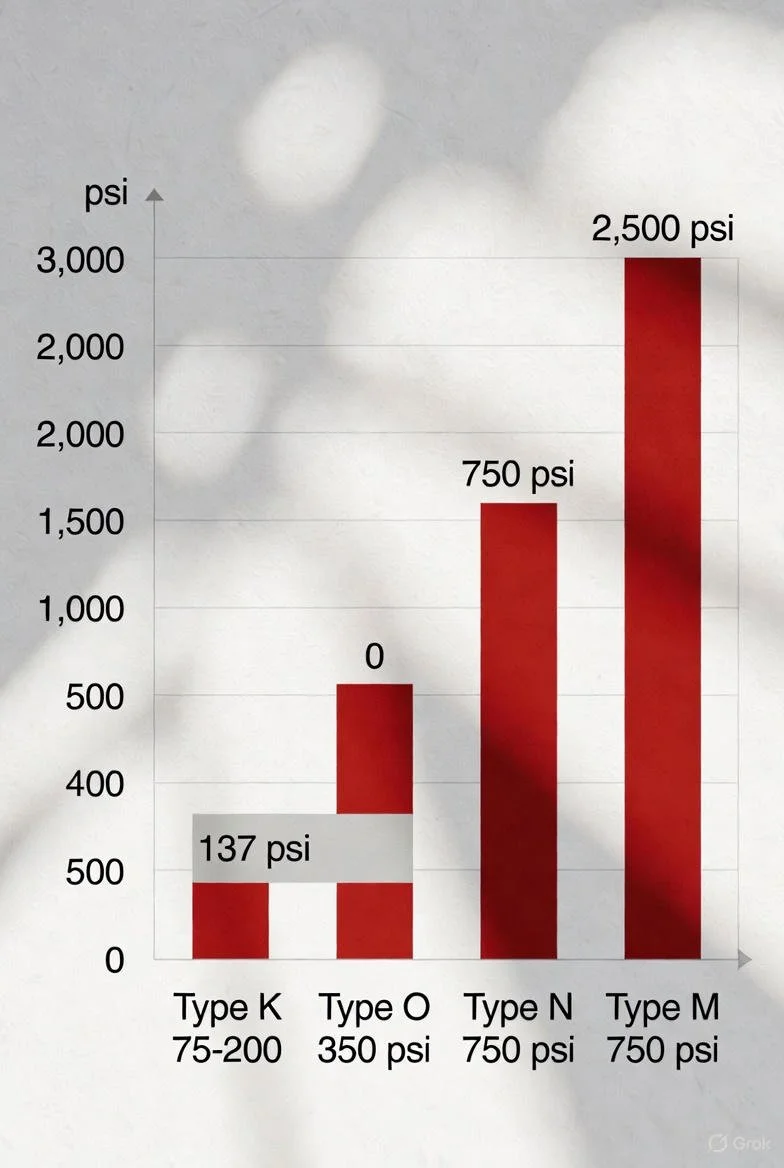

Modern ASTM C270 Mortar Types

Contemporary mortar in North America is classified by minimum 28-day compressive strength:

Type K – 75–200 psi (rarely produced commercially; closest to pre-1850 mortars)

Type O – 350 psi (standard for historic restoration)

Type N – 750 psi (general-purpose modern mortar)

Type S – 1,800 psi (high-strength for reinforced or below-grade applications)

Type M – 2,500 psi (highest strength for severe loading or exposure)

Performance Differences Between Lime and Portland-Dominant Mortars

Compressive strength: 50–400 psi in historic lime mortars versus 750–3,000+ psi in modern cement-rich mixes

Vapor permeability: very high in lime mortars; significantly lower in Portland-dominant mortars

Flexibility: high in lime systems; low and brittle in high-cement mixes

Self-healing: present in lime mortars through continued carbonation; virtually absent in Portland mortars

Freeze-thaw durability: excellent in permeable lime systems; compromised when strong, impermeable mortars trap moisture against brick faces

Consequences of Excessive Mortar Strength

When modern high-strength mortars are used with older, softer brick, the mortar becomes the rigid element and the brick becomes sacrificial.

Moisture trapped behind impermeable repointing leads to face spalling

Differential movement concentrates stress on brick units rather than the joints

Historic buildings repointed with Type N or stronger mortar frequently develop accelerated deterioration within a few decades

Appropriate Mortar Strengths by Application

Repointing pre-1900 soft brick: Type K (75–200 psi) or site-mixed 1:3 lime-putty:sand

Restoration of 1850–1920 masonry: Type O (350 psi) or NHL 2.0–3.5 hydraulic lime

New construction intended to match historic fabric: Type O or moderate-strength hydraulic lime

Modern load-bearing or reinforced masonry: Type N or S as required by structural design

Foundations, retaining walls, or seismic zones: Type S or M where high strength is structurally necessary

Conclusion

Mortar strength is never a case of “stronger is better.” In historic masonry, replicating the original low compressive strength and high permeability remains the most reliable path to long-term preservation. Using appropriately weak, breathable mortars allows walls to accommodate movement and moisture exactly as their builders intended, ensuring durability measured in centuries rather than decades.