Common Historical and Modern Brick Bond Patterns: An Educational Overview

The way bricks interlock in a wall is called a “bond.” Historically, the choice of bond was driven by structural necessity first and aesthetic preference second. Before the widespread use of steel and concrete framing, load-bearing brick walls relied entirely on the overlapping of units to resist shear, compression, and lateral forces. The same patterns that provided strength also created distinctive textures that we still recognize in centuries-old buildings today.

Key Structural and Historical Brick Bonds

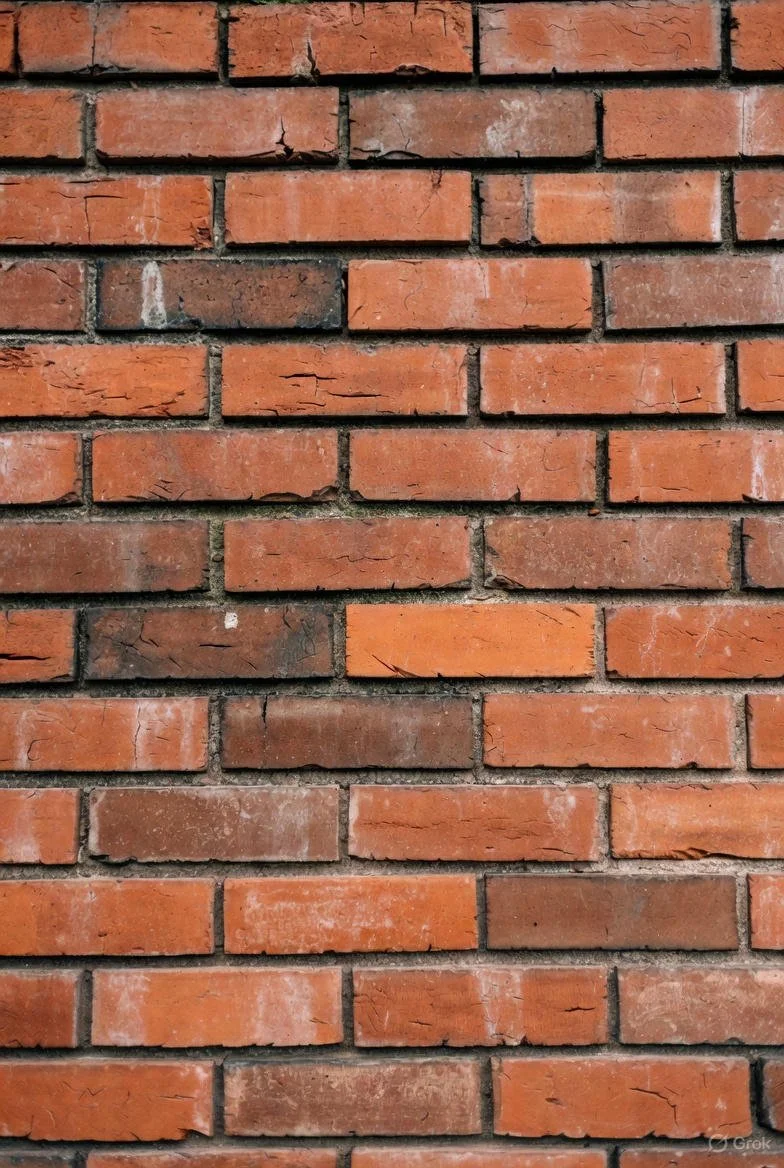

Running Bond (Stretcher Bond)

The simplest and most common modern bond.

Every course consists entirely of stretchers (bricks laid lengthwise), with vertical joints offset by half a brick in each successive course.

Extremely common in 20th-century cavity-wall construction because it works perfectly with wall ties and insulation.

Structurally weaker in solid (pre-1900) walls unless metal ties or headers are introduced every few courses.

Visually creates strong horizontal lines; often chosen today for German Smear and mortar-wash finishes because the recessed joints remain consistent and easy to tool.

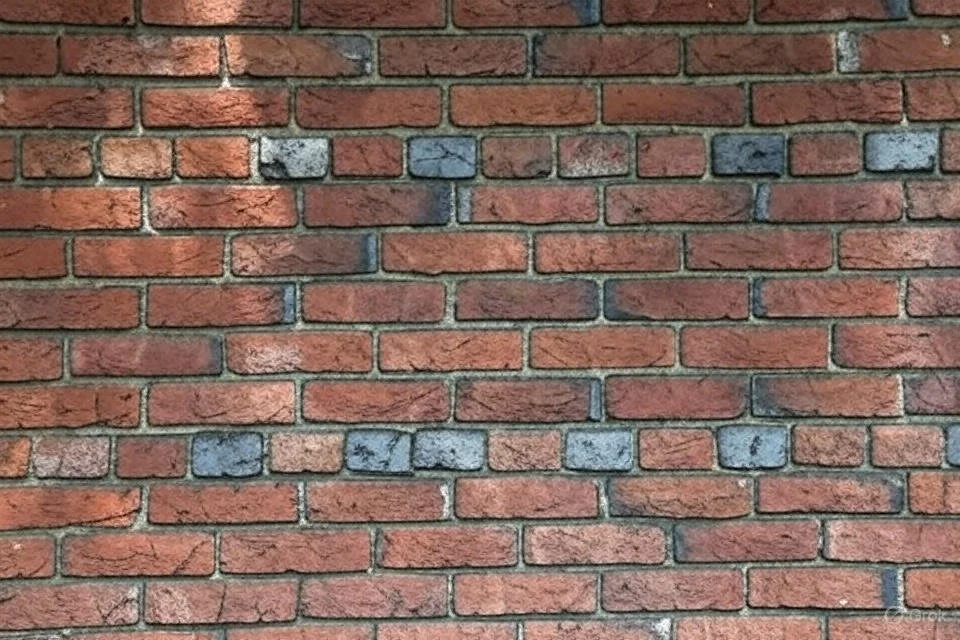

English Bond

Alternates courses of headers (bricks laid width-wise) and stretchers.

Considered one of the strongest historical bonds for solid load-bearing masonry.

Widely used in Britain and colonial America from the 17th through early 19th centuries.

The header courses tie the wythes (layers) together, giving excellent transverse strength.

Produces a distinctive pattern of alternating rows: one row shows only brick ends, the next row shows only sides.

Flemish Bond

Each course contains alternating headers and stretchers in the same row.

Every header is centered on a stretcher above and below, creating a woven appearance.

Popular in Georgian and Federal architecture (especially 18th-century Britain and American East Coast).

More labor-intensive than English bond but considered more refined.

Variants include “monk bond” (two stretchers between headers) and “Dutch bond” (similar but with slight offsets).

Common Bond (American Bond)

A practical 19th-century American adaptation.

Typically five or six courses of stretchers followed by one full header course.

Allowed faster construction than pure English or Flemish while still tying multiple wythes together.

Extremely widespread in U.S. urban row houses and industrial buildings 1850–1920.

The periodic header course creates subtle horizontal banding that many homeowners now highlight with German Smear techniques.

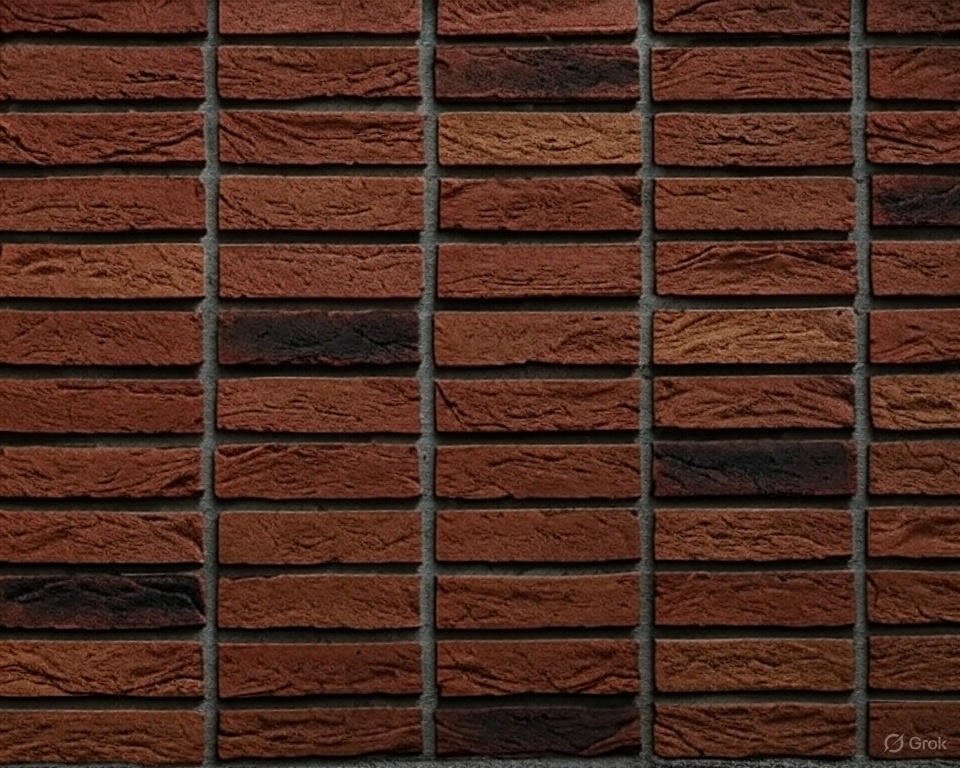

Stack Bond

All bricks aligned vertically with continuous perpendicular joints.

No overlapping whatsoever in the traditional sense.

Structurally very weak in load-bearing situations; requires heavy reinforcement or steel framing today.

Purely decorative in modern use; popular in mid-20th-century modernism and contemporary accent walls.

When used with thick mortar joints and German Smear, the grid-like pattern becomes strongly pronounced.

Herringbone Bond

Bricks laid at 45-degree angles in zigzag pattern.

Historically used for paving (floors, courtyards, roads) more than walls.

Occasionally appears as decorative panels within larger walls (Tudor and Arts & Crafts revivals).

High waste factor and labor cost; rarely used in load-bearing contexts.

Basketweave Bond

Groups of two or three bricks laid horizontally, alternated with the same number laid vertically.

Again primarily a paving pattern, but sometimes inset as decorative friezes or garden walls.

Creates a woven mat appearance; visually striking when lime-washed or German Smeared.

How Bond Choice Affects Mortar-Wash and German Smear Finishes

Bonds with deep, consistent recessed joints (running bond, common bond) accept heavy German Smear most easily because mortar can be thickly applied and tooled.

Flemish and English bonds present more exposed header faces, causing a slightly busier texture after smearing.

Stack bond creates bold grid lines that become dramatic when mortar is smeared and partially wiped away.

Older lime-mortar walls in historic English or Flemish bond often show natural efflorescence and patina that interact differently with modern Portland-lime smears than 20th-century hard mortar in running bond.

Conclusion

Brick bond patterns are a direct record of structural requirements, labor economics, regional material dimensions, and evolving aesthetic taste over centuries. From the ultra-strong English bond of the 1700s to the minimalist stack bond of today, each pattern influences not only engineering performance but also the final appearance when traditional or contemporary finishes such as German Smear or limewash are applied. Recognizing these historic bonds helps us read the age, origin, and construction logic of masonry buildings wherever they stand.